Hungarian-British writer David Szalay’s Flesh has won the Booker Prize for 2025, further strengthening a spate of award-winning fiction preserving the spectre of post-war/ post-socialist Europe in the public imagination, in just the decade since Svetlana Alexievich won the Nobel Prize in literature.

Szalay has a Hungarian father and, after time in the U.K. and Belgium, moved to the Central European country. Flesh is also closely tied to the country: its protagonist returns there and scenes unfold amid late-socialist urbanism.

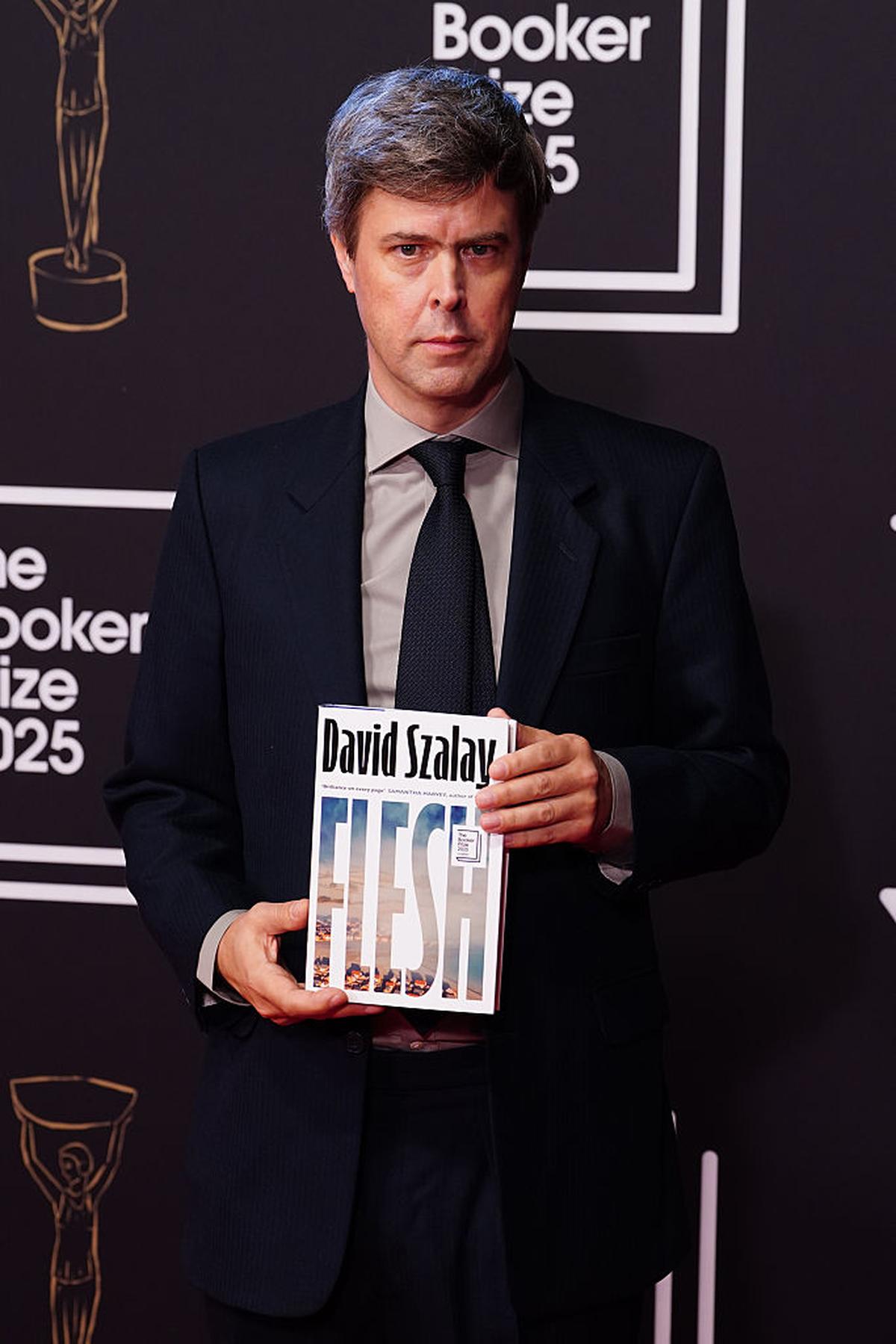

Author David Szalay whose novel Flesh won the Booker Prize 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

It would seem this particular condition hasn’t ended but has in fact become a climate. Institutions carry on, often barely, and while there are freedom and dignity in practice, they’re mediated by everyday systems reminiscent of the erstwhile Soviet Union’s heyday. In their celebrated novels, László Krasznahorkai (also from Hungary, and who has been awarded the literature Nobel this year), Olga Tokarczuk, Peter Handke, Dubravka Ugrešić, Georgi Gospodinov, Jenny Erpenbeck, Mircea Cărtărescu, Serhiy Zhadan, and Kapka Kassabova have all chosen forms to match their materials — of long circuits, fragments, speculative frames, and often plain diaries of passage. Their books don’t promise resolution but simply keep a ledger of how people maintain lives when history moves on, leaving them to work out the details.

Resonant themes

A particularly resonant theme is systems changing but not the furniture. Consider Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming by Krasznahorkai, which turns a provincial town into a nearly lifeless machine with the cultural house staging events, the police enforcing order, the local press manufacturing anticipation, only for nothing of substance to arrive.

2025 Literature Nobel laureate Laszlo Krasznahorkai

| Photo Credit:

WireImage

Likewise in Erpenbeck’s Kairos, where the Wall falls, yet while the institutions of the former East Germany dissolve on paper, the habits they produced in people, from deference to the hunger for recognition, endure. Cărtărescu’s Solenoid provides the pre-history to this fate in a late-communist Bucharest that’s an apparatus of inspections and petty humiliation, all to train in the local population a posture of inwardness. It seems after 1989, that posture didn’t just evaporate but instituted in citizens a wariness of new freedoms.

Jenny Erpenbeck, whose novel Kairos won the International Booker Prize 2024.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Another theme centres on mobility. Tokarczuk’s Flights is an ethnography of motion, of bodies in transit in airports and ferries and through museums and cabinets of curiosities. Yet, Flights doesn’t celebrate movement so much as measures its costs. Ugrešić’s The Ministry of Pain does something similar for the former Yugoslavia, with its visas, teaching contracts, work permits, and residency papers, and ultimately the drain of explaining oneself to an outsider that won’t recognise trauma unless it’s in action.

Kassabova’s Border stands on the ground where crossings were once forbidden and shows how routes and smugglers survive rule changes. For all three, mobility is work rather than freedom, and for which you’d better have your papers in order.

Serving nostalgia

Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov, whose novel Time Shelter won the International Booker Prize 2023.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Time Shelter by Gospodinov also throws up nostalgia as a way to govern a people, with clinics that recreate past decades becoming popular only for elections and new referendums to formalise a backward turn, accentuated by the book’s speculative style. While the travellers in Flights resist the precarities of their present by staying on the move, they’re still visible in what the museums choose to display, ergo what nations choose to monumentalise. Kairos similarly documents who gets to tell the story of the GDR, who gets work as a witness, and who is told to move on.

Finally, we have language, authority, and the idea that the two are often the same thing. In The Moravian Night, Handke moves through Balkan spaces where most speech is only official narrative. He worries about the boundary between testimony and performance and forces the reader to sit with the uncertainty of what can be said without being pressed into someone else’s service.

Ugrešić’s The Ministry of Pain examines this scene from another angle, mapping how the literary market sorts Balkan voices by their appeal to Western expectations. Ugrešić is cold-eyed about the demand for tidy accounts of war and exile and about the compromises writers make to be published. In the same vein, Cărtărescu’s Solenoid retreats from state language into private architecture but still without losing sight of the civic pressure that prompted the retreat.

Ongoing wars

War is of course always ongoing in these pages. The Orphanage by Zhadan sits close to the frontline and writes from checkpoints and severed phone lines through constant interruption. Kassabova shows the long tail of gun-laden borders that keep producing fear and opportunity after the armies leave. And while Krasznahorkai’s towns feel demilitarised, they remain garrisoned by bureaucracy. Read together with Erpenbeck’s Kairos, it seems the people are still fighting the war, just that the enemy is the friction that stayed behind.

Szalay’s Flesh strengthens this revival of sorts by recording late-socialist housing and thin public services against Western-style consumption. There’s administrative gatekeeping once again but also the fraying of a diaspora, in terms of languages lost across borders and meetings staged on neutral ground. Without pronouncing a thesis, Flesh shows how lives become synchronised to institutions that changed in all but their tempo.

These books are also stripped of melodrama, use a low register, lengthen outcomes until they’re indistinguishable from destiny, pare scenes down to hard edges, preclude sentiment, and meticulously record every small transaction between nativity and exile. The common effect is to avoid consoling frames and to keep from vindicating dignity.

Three decades have passed since the political ruptures of 1989-91, long enough for writers to observe a generation grow up inside the new order. There have also been geopolitical pressures on borders, including the 2015 refugee crisis, the rise of nationalist parties, the institutionalisation of “memory laws”, and the return of large-scale war to Europe. In these conditions, the questions of what counts as European and how state socialism ought to be remembered have again become relevant, aided by an international reading market more curious about intra-European peripheries and literary prizes that foreground translators’ labour.

Post-war and post-socialist narratives from Eastern and Central Europe add a record of how large events settle into ordinary life, and thus constitute a more relevant memorialisation in their own right. Scholarly histories of World War II and the fall of the Soviet Union fixed the sequence and scale of violence and reform, centring institutions, leaders, treaties, and borders, whereas these recent novels muster a counter-archive of small, repeatable situations that those accounts could never hold. Thus, they don’t correct the record so much as cut its judgment to the size of what people can actually do.

mukunth.v@thehindu.co.in

Published – November 14, 2025 03:15 pm IST